On the bleak autumn Saturday of November 7, 1903, American businessman, inventor, and art collector, William Lukens Elkins, died in his summer home at the age of 71. Over the course of his life, Elkins operated a produce business, founded one of the first oil refineries in Philadelphia, and partnered in multiple street car and railway companies across the east coast; all grand endeavors that allowed him to become incredibly wealthy. In his sixty page will, on the topic of his children and grandchildren, he stated that,

"It is my intention... to maintain trusts during their respective life times, of all descendants of mine in existence at the time of my death."

Elkins' fortune was not squandered, as most of his grandchildren put it to good use. One, upon death, gave his entire book collection to the Free Library of Philadelphia. Another helped found the Tyler School of Art. Others had successful creative careers as a playwright, artist, and Broadway producer. Elkins' also donated $240,000 to the Masonic Home of Philadelphia, to be used on the erection of a female orphanage. His home and it's belongings were bequeathed to his widow, who also recieved $100,000, including an additional $100k annually. Even his coachman and valet were given a thousand dollars each.

|

| William Lukens Elkins in 1899. |

But a fortune wasn't the only thing Elkins left behind. Only eight miles away from his home, at the intersection of Broad and Girard streets in downtown Philadelphia, Elkins owned a beautiful brownstone mansion that was built eleven years before his death, in 1892. His mansion, cold and abandoned, would soon have more guests than ever intended.

The details are fuzzy, but at some point after Elkins' death, the mansion was sold to an Adolph Segal, a business man, like Elkins, who began making plans to convert the mansion into a hotel. This hotel was to be a melting pot of international food, art, music, and style, all to provide travelers with a premier and exotic experience. It would include a luxurious cafe, a pipe organ, an art gallery, exuberant decorations, the most elaborate grotto in the United States, and much, much more. It would be magnificent. It would be monumental. It would be majestic.

|

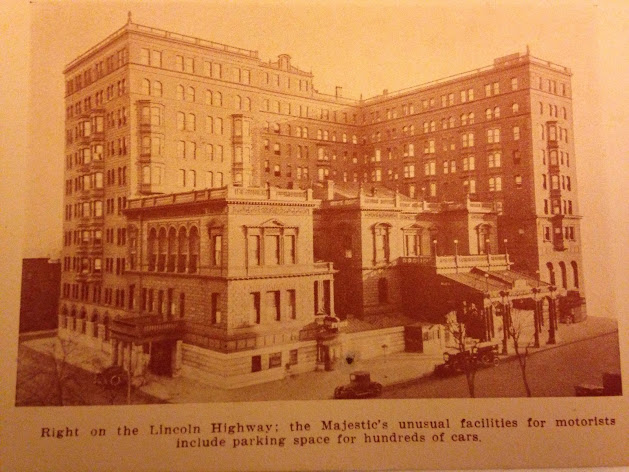

| Postcard of the Hotel Majestic from around 1912. |

Segal quickly turned Elkins' original four-story mansion into the entrance and main hub of the Hotel Majestic; and, around the back, built an additional ten-story building to host over 400 guest rooms. A night in the Majestic cost only $2 (or about $59 in 2021), but guests also had the option of paying monthly, which started at $60 (or about $1700) per month and upwards. Special attention was made for transient guests who were traveling from all around the world on long business trips to the bustling city of Philadelphia. So many travelers came, in fact, that the Majestic's "Viennese" grotto had seen 37,000 visitors in its first 18 days of opening.

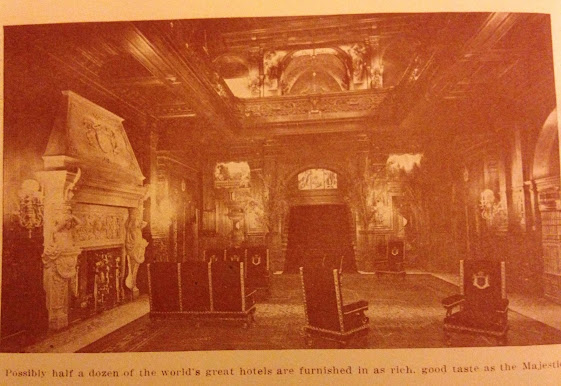

|

| Photo of the mansion's interior leading into the hotel from about 1912. |

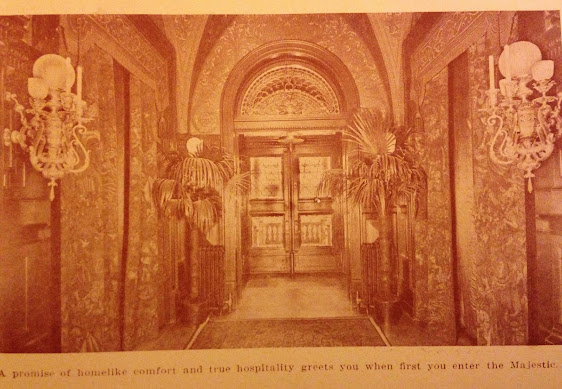

|

| Presumably the entrance of the mansion from the same postcard. |

It appears that the hotel's name isn't very consistent throughout its existence--going back and forth between "Hotel Majestic" and "Majestic Hotel"--but the sign at the top of the hotel reads in big, unmistakable letters, "HOTEL MAJESTIC". And so, that's what it was called, at least some of the time.

A newspaper clipping from the April 17th, 1908 edition of the

Philadelphia Inquirer includes an advertisement in the "Amusements"

section for entertainment at "Hotel Majestic". The ad highlights a Hungarian singer who goes by the name of Mamzelle Madelaine Disston. She's the "newest great big hit in the city" and she will be dressed in her "native" costume singing songs from the era's top performers. Szalay, "the great Hungarian violin virtuoso", and three other orchestras will accompany her on Saturday night, and every night next week. Dinner is served every evening from 5:30pm to 9:00pm, and costs $1 in the Grotto and $1.25 in the Cafe.

|

| Philadelphia Inquirer clipping from 1908. |

There is, unfortunately, no more information about M. Disston and Szalay; so maybe they weren't the "great big hits" they were made out to be. It looks like the newspaper advertising did it's job though, because that's about all that's left of the Majestic--as well as a few postcards and souvenirs.

In 1905, when the Majestic was still brand new, lithograph-on-tin art plates were quite popular and commonly sold as souvenirs. They were small, decorative plates with portraits of beautiful young women and relaxing outdoor scenery that were mass produced in the likeness of the more rare and expensive Royal Vienna porcelain plates. These cheaper, tin plates were tagged with information about the place they were being sold from and used as a sort of in-home advertising. The Majestic Hotel began to sell these souvenir plates as well, and I am recently the proud owner of one.

|

| Only $40 on eBay, or about $1.30 in 1905. |

|

| Perfectly crisp blue lettering on the back. |

I'm also the owner of another piece of the hotel's mysterious history.

At some point between 1934 and 1963, someone was doing work on the upstairs floor of my childhood home, long before my parents were born. They were eating red-dyed pistachios--imported from Iran and dyed to cover up ugly look shells--and most likely smoking a cigarette. I know this because, while removing the hideous popcorn ceiling in the dining room, my dad found pistachio shells and a matchbook. The matchbook, covered in dust and barely holding itself together, advertised something I had never heard of before.

|

| Majestic Hotel matchbook, uncovered in 2018. |

The matchbook promotes a newly remodeled "Majestic Hotel" that includes 350 rooms, two air conditioned restaurants, televisions, a cocktail lounge, a dubonnet room, and other fancy things. It has an golden emblem on the front with the image of a man wearing a crown and the slogan "Where you are king". A relic from the same hotel, now decades into the 20th century. This matchbook is the first time I heard of the Majestic, and it's been on my mind ever since I found it. I did some light research over the years, to find out what happened to this majestic building, but this is the first time I'm actually putting it all together.

The Majestic has a long history that seems to be mostly forgotten. Scattered newspaper articles tell stories about special guests who stayed at the Majestic and the important events that were held there. Here are a few notable stories:

In 1911, during the World Series, popular baseball players from the former Philadelphia Athletics and the New York Giants stayed at the Majestic before the game. It wasn't notable then, but it adds another piece to the puzzle of the hotel's history.

In 1923, surprise prohibition officers raided the Majestic, arrested a cafe manager, and found two cases of champagne and eighteen bottles of burgundy.

In 1946, various hotel workers across Philadelphia--including those from the Majestic--went on strike asking for an 18¢ raise from their current 7¢ an hour wage, as well as a decrease from forty-eight hour workweeks to forty. This left over 400 guests at the Majestic without service, and the employees eventually went back to work without getting their raise.

These events all help to paint a bigger picture, but one story in particular might point to the beginning of the end for the Majestic. The story of Adolph Segal, the man who originally bought the mansion from William Lukens Elkins' family and turned it into the Majestic.

|

| New York Times clipping from 1907. |

On September 17, 1907, Adolph Segal was indicted by a grand jury for the apparent failure of the Real Estate Trust Company of Philadelphia. Segal was charged with multiple cases of conspiracy, embezzlement, and the unlawful receiving of money. The president of RETCO, Frank Hipple, had also been charged with the embezzlement of $50,000, which led to his eventual suicide. Segal was rumored to have had a "hypnotic influence" on Hipple, directly causing his suicide, but he was freed of indictment in 1908 and found to have no criminal intentions. Though he was free for now, Segal continued to have issues with his finances, and the law.

In March of 1914, Segal was involuntarily declared bankrupt. He had accrued an incredible amount of debt through his frivolous spending at the Majestic, his sugar refinery, and various other questionable business ventures. He had apparently spent $20,000 on a piano for the Majestic, and $100,000 for more elaborate

decorations. His total debt amounted to $2,893,731, and he only had $150 in assets in the form of clothes and jewelry. Months after the bankruptcy, he was pronounced insane.

|

| September 18, 1914 issue of Evening Ledger. |

Segal was diagnosed as insane by two physicians. His meteoric financing of so many large scale businesses had likely taken a toll on his mental health and put him in the hospital. He couldn't afford to be sent to a private asylum, due to the bankruptcy, and he also couldn't continue being kept in the hospital, as his stay there was draining money from his wife and family. So, having only one option, he was sent to the public Norristown Asylum. His son apparently took over ownership of the Majestic, and that might be the catalyst for its downfall.

Segal spent two and a half years in Norristown, labeled as "hopelessly insane", but was eventually released on October 12, 1916, at the age of 62. He vowed to pay all of his debt back to his creditors, and was more than ready to get back in business. His wealthy friends had set up a fund to enable him to work again and he was quickly on his feet. But he was arrested in 1925 for passing a worthless check of $400, and that's the last newspaper article I can find about him.

So first, it was the mansion of a refined oil pioneer. Then, a major attraction for early 1900s tourism in Philadelphia. And finally, a hotel of choice for travelers of all kinds throughout it's tenure of well over 50 years. The Majestic was, unfortunately, bought by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority in 1963, and shut down for a "southwest urban renewal project" by Temple University. But it wasn't demolished immediately and Temple's plans fell through. In 1965 it was said to be used for "office-type commercial structures" instead, but that didn't happen either. The Majestic remained in limbo, slowly falling apart, until 1971, when it was finally demolished and eventually turned into various fast food restaurants and gas stations. It's currently a KFC and Checkers, of all things.

|

| Was it worth it? |

But I won't forget the Majestic. It doesn't deserve to be erased from history like so many things unfairly are. So in order to keep its memory alive, I am archiving everything I could find about it--the stories, the pictures, and the people--here, all in once place, in honor Philadelphia's lost marvel. Below are all the decent photos I found while researching the Majestic, and at the very end, links to all of my

incredibly helpful and interesting sources. While a monarchy is certainly out of date by today's standards, hopefully the Hotel Majestic can always be the place "where you are king".

|

| Ballroom, 1925 |

|

| Northeast corner hallway, 1925 |

|

| Lounge, 1925 |

|

| Northeast corner hallway, 1925 |

|

| Press photo from 1944 of a fire on the roof of the mansion. |

|

| 1963 |

Disclaimer: All the information presented here is made up of scattered, unscholarly articles, old newspaper clippings, postcards, and images sent from readers. I likely got many things wrong about the hotel's spotty history, but this is the best I could do at piecing it all together. If you have any more information, please contact me at antcedrone95@gmail.com.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Lukens_Elkins

https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/21788/william-lukens-elkins?utm_source=pocket_mylist

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1903/11/15/290339102.pdf

https://www.interestingpennsylvania.com/2015/01/postcards-former-majestic-hotel.html

https://www.newspapers.com/clip/19026442/the-philadelphia-inquirer/

https://outlet.historicimages.com/products/nec00651

https://lcpimages.org/inventories/jennings/hotels/hotels.htm

https://www.philadelphiabuildings.org/pab/app/pj_display.cfm/83274

https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83045211/1914-09-18/ed-4/seq-14/

https://digital.library.temple.edu/digital/collection/p15037coll7/id/1705/

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217542451.pdf

https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1925/08/21/101676426.html?pageNumber=30

https://www.in2013dollars.com/us/inflation/1905

"Quaker Ladies Hold A Banquet Too

ReplyDeletePhiladelphia, Jan. 17 — The Ladies' Quaker City Motor Club held' its annual banquet last week in the clubrooms at the Hotel Majestic. Gold and white, the club colors were prominent in the decorations, and were repeated in the handsomely designed menu cards. During the affair a cable message was received announcing the election of the L. Q. C. M. C to associate membership in the Royal Automobile Club of London. The committee in charge was composed of Mrs. Edward B. Finck, Mrs. Joseph J. Martin, Sr., Mrs. Joseph J. Martin, Jr., Mrs. Samuel E Baily2, Mrs. Charles Snyder and Dr. Katherine Sweeney"

The Automobile, 1910. Quaker Ladies Hold A Banquet Too. 20 January 1910, p175 https://archive.org/details/Theautomobile22/theautomobile22/page/n185/mode/2up?q=Martin&view=theater